How Does the Art Work of Ancient Greece Reflect Their Military Conquests?

Warfare was a common occurrence in Greece from the Neolithic Period through its conquest past Alexander the Swell and until its conquest past the Roman Empire. Considering of this, warfare was a typical theme in many pieces of ancient Greek art. Many works of fine art, like the Doryphoros or the chryselephantine statue of Athena Parthenos, used military objects in their limerick, and many others, like the Chigi vase, had warfare every bit their primary subject. Ancient Greek art is an of import attribute of not merely the history of art, but the history of warfare as well, due to its frequent spot on many works of ancient Greek art. As each different menstruation in Greek history occurred, more and more types of art formed, as well as differing depictions of warfare.

Statuary Historic period [edit]

In Minoan art, warfare is not explicitly shown, simply rather different interpretations were made that could tie into warfare. For example, bull-leaping was an activity Minoan men did and the struggle between human and balderdash could be a depiction of warfare.[one]

Archaic menses [edit]

During the Primitive Period, depictions of warfare in Greek fine art held importance in status markings, and also provide insight as to the trading markets during this era. For instance, the Arezzo 1465 vase, an Cranium volute krater attributed to Euphronios in the Late Archaic Era, depicts an amazonomachy, and was found in the Etruria region, indicating the expanse of the trade networks. Warfare every bit a status symbol further solidifies a reasoning behind this trade, since whatsoever art with warfare depictions on it thereby becomes a sort of luxury detail sought after by those wishing to elevate their own status because aspects and physical areas of Greek club tended to extol armed services prestige and virtue. Proving oneself in boxing distinguished one from the others and brought glory (klèos) to their families;[ii] consequently owning any fine art depicting warfare displayed one'southward wealth and elite status.

During the Archaic menses many artists began to draw the hoplite formation in art. Representations of the hoplite phalanx give historians a look into how the Greeks used this style of warfare in battle. Hoplites can be identified by their spear and their shield as well every bit their position next to other soldiers. One of the most popular representations of the hoplite phalanx is in the Chigi vase. The hoplite formation is portrayed on many unlike types of pottery such equally the Dinos, the Krater, and the Alabastron; and information technology many dissimilar styles such as black figure and white ground.

During the Archaic period there are pieces of artwork that depict the aulos player. 1 of the most prominent pieces show how the aulos player helped keep the hoplite soldiers in pace by playing them into battle. With the help of the aulete, they were able to keep their shields close together to prevent the opposing phalanx from penetrating their ranks.[3]

Co-ordinate to Richard Neer, at the temple of Hera "the Primitive votives are masculine and martial: helmets and 'smiting figurines'".[4]

Classical period [edit]

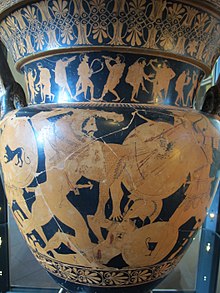

Calyx-Krater by the Painter of the Berlin Hydra

The Classical Menstruum involved many scenes relating and alluding to the Persian wars.[5] This allusion can include some of the numerous depictions of mythical battle scenes such every bit amazonomachies, gigantomachies, and centauromachies during the menstruum.[v] Such themes and mythological scenes can be seen in depictions like the one on the Calyx-Krater by the painter of the Berlin Hydria depicting an Amazonomachy, or the Gigantomachy by the Suessula Painter.

The starting time quarter of the Classical Menses involved a lot of warfare, including the Western farsi Wars. Many Greek cities were sacked by the Persians during the second Persian War, taking a toll on several city-states. Themistoclean Walls were built quickly post-obit the Greek victory of the 2nd Persian Wars, using destroyed sculptures and buildings to construct them. These re-purposed stones used in the building of Themistoclean walls is known as spolia. The Classical Period was also a fourth dimension of Athenian command over Hellenic republic, powerwise, merely also military wise and Athenian pottery was the near popular and well-spread over Greece.

Hellenistic tower from Achinos, Phthiotis

Hellenistic Menses [edit]

Aside from a build upwardly of compages, other aspects of Greek civilisation, such as grave markers, were also becoming awe-inspiring. A majority of sculpture during this period was more than chiliad and historic triumph and the power of the Greeks equally a whole community or civilisation.

Additionally, military machine monuments dedicated to the gods continued to remain prominent in Hellenistic culture. One such monument is the Neorion at Samothrace, a monumentalized send dedication within the Sanctuary of the Great Gods at the Greek island of Samothrace. Such architectural monuments demonstrate the continued importance of religiosity in fine art regarding warfare, even in a sanctuary concerned with larger mystery cults unrelated to war. This is a connected theme reflected in threads from the depiction of myth in the Archaic and Classical Periods, to the bull-leaping of the Minoans in the Bronze Age, which is considered potentially both religious and militaristic in nature.[half-dozen]

Alexander the Corking rose to prominence past winning the state of war which saw the end of the Farsi Empire. Paintings and sculptures depicting battles and participants in the war were common in this period.

References [edit]

- ^ Molloy, Barry (2012). "Martial Minoans? War As Social Procedure, Practice and Outcome in Bronze Age Crete". The Annual of the British Schoolhouse at Athens. 107: 87–142. JSTOR 41721880.

- ^ Fine art, Writer: Department of Greek and Roman. "Warfare in Aboriginal Greece | Essay | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art". The Met'south Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . Retrieved 2017-12-03 .

- ^ Hurwit, Jeffrey K. "Reading the Chigi Vase." Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, vol. 71, no. 1, 2002, pp. one–22. JSTOR, JSTOR, world wide web.jstor.org/stable/3182058.

- ^ Neer, Richard. Greek Art and Archeology. Thames & Hudson.

- ^ a b ŞAHİN, Reyhan. 2017. "Representations of Mythological State of war Scenes northward Attic Figure Pottery and Approaches in Research." Social Sciences Review Of The Faculty Of Sciences & Messages Academy Of Uludag / Fen Edebiyat Fakültesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi 19, no. 32: 259-285. Academic Search Consummate, EBSCO host (accessed November 28, 2017).

- ^ "Troy". Encyclopedia Britannica . Retrieved 2017-12-03 .

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Warfare_in_ancient_Greek_art

0 Response to "How Does the Art Work of Ancient Greece Reflect Their Military Conquests?"

إرسال تعليق