Iceland Is Officially Worshiping Norse Gods Again

How Republic of iceland recreated a Viking-age organized religion

(Image credit:

Gunnar Freyr Steinsson/Alamy

)

The Ásatrú religion, ane of Republic of iceland's fastest growing religions, combines Norse mythology with ecological awareness – and it's open up to all.

P

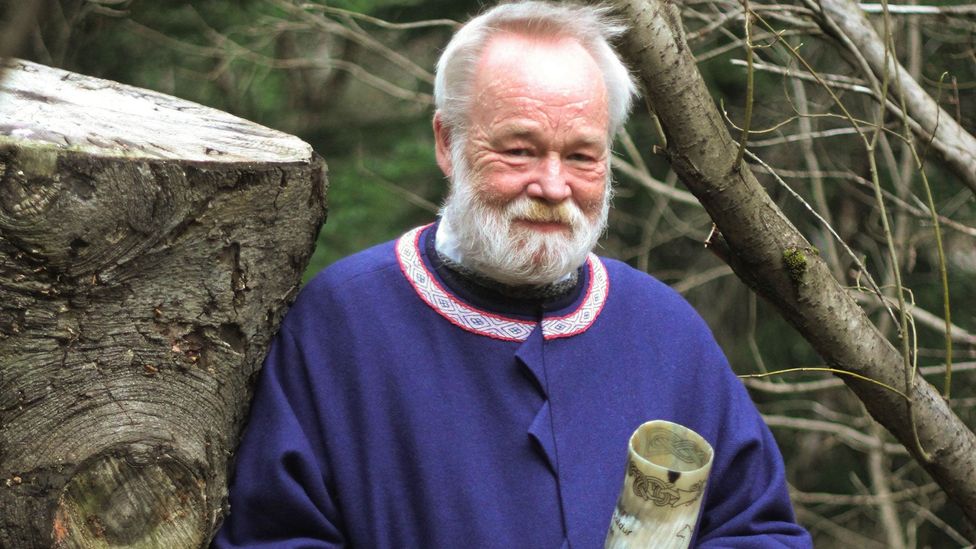

Priest Hilmar Örn Hilmarsson rummaged around in his blue woollen robe and fished out two cans of warm Icelandic lager. "Beer?" he asked, handing me ane of the tepid tins, which frothed violently as I pulled the band. "Skál," said the priest, a mischievous glint in his pale blue eyes. "Skál," I repeated, and we slurped our overflowing lagers.

Those weren't the showtime beers of the day. Earlier that afternoon, Hilmarsson had poured pilsner into a bull's horn and passed information technology around his congregation; a motley crew of characters, some of whom looked like they were extras from Game of Thrones, others straight off the phase of a heavy metal concert. Most, though, were dressed in regular dress befitting of a breezy mean solar day in Iceland.

The congregation, which comprised a few dozen souls, including a Buddhist and a Hindu guest, had gathered near a sandy beach on the outskirts of Reykjavik, adjacent to the city's domestic drome, to celebrate the first mean solar day of the Icelandic summer. It was 25 April, slightly dank and mostly overcast. Rain looked likely.

The Ásatrú Association of Iceland is currently ane of the state's fastest growing religions (Credit: Gunnar Freyr Steinsson/Alamy)

You may also exist interested in:

• Why Icelanders believe in elves

• The planet's most extreme cuisine

• Are Lithuanians obsessed with bees?

The 'blót', as the irresolute-of-the-flavor anniversary is known, began with the lighting of a modest burn, which flickered in the breeze as the congregation listened to Onetime Norse poetry and raised the beer-filled horn to laurels the Norse gods. Elsewhere on the island, similar ceremonies, I was told, were taking place.

The blót had been organised by the Ásatrú Association of Iceland, a pagan religion group that is currently ane of the country'due south fastest growing religions, having nearly quadrupled its membership in a decade, albeit from a depression base of operations of 1,275 people in 2009 to 4,473 in 2018.

Hilmarsson is the faith's leader. A warm, charismatic human in his early 60s, he cuts a debonair figure with his white hair, white beard and nicotine-stained white moustache. Hilmarsson was elected equally high priest in 2003 and jokingly claims to take been "stupid enough to say yep". He also works as a prominent musician, and has collaborated with some of Iceland'due south best-known artists, including Björk and Sigur Rós.

"The high priest and the composer piece of work hand in hand," he told me, puffing on a cigar. "At that place'due south a search for harmony in both."

Hilmar Örn Hilmarsson was elected high priest of the Ásatrú Association in 2003 (Credit: Gavin Haines)

The Ásatrú Association is tricky to ascertain because information technology has no stock-still beliefs ("The suspension of disbelief is more than accurate," Hilmarsson explained, somewhat surreally). The group does, however, subscribe to local folklore, and meetings typically involve recitals from the Sagas of Iceland, a literary catechism written during the 13th Century, only based on fantastical tales of dear, loss and heroism from as far back as the 9th Century.

"People in the year 950 didn't have a lot to practise, so they sat around fires telling stories," explained Haukur Bragason, a young, well-coiffed Ásatrú priest who was attending the blót. "They were the Netflix of old times."

The Ásatrú religion also celebrates One-time Norse mythology and its pantheon of morally ambiguous deities – gods such as Odin, Thor and Loki – that came to Iceland during the Viking Age, when the isle was settled by Norwegian farmers looking for new pastures. These deities were worshipped across this 'state of fire and ice' until the twelvemonth 1000, when, under pressure from the influential Norwegian crown, the state abased heathenry and adopted Christianity.

But in 1972, a group of artists, led by the belatedly sheep farmer and poet Sveinbjörn Beinteinsson, cooked upward a plan to reboot the one-time infidel faith. Over meetings in cosy Reykjavik java shops, the group established the Ásatrú Association and the post-obit year successfully lobbied Iceland's government to recognise it every bit an official faith.

The story goes that while the minister of justice and ecclesiastical affairs, Ólafur Jóhannesson, considered the matter, a powerful storm striking Reykjavik. "Lightning struck the ability station and at that place was a blackness out," Hilmarsson explained. "People thought it was Thor showing his might [and then] the minister relented."

A new organized religion was born.

Ásatrú Association members marker the changing of the seasons with a blót, which usually involves lighting a burn and listening to Old Norse poetry (Credit: Bjarki Reyr/Alamy)

Although the Ásatrú Association has no doctrine as such, it does promote virtuous behaviour. "It'south well-nigh beingness honest, upright and tolerant," Hilmarsson said. "Respect for nature is also important. You have to make sure you live in harmony with nature."

The association has been concerned with the environment from the beginning. "[Beinteinsson] was into ecology before most people were familiar with the concept," said Hilmarsson, who believes increased sensation of climate modify and biodiversity loss is alluring more than people to the religion. "I think this is a good for you reaction confronting that."

The clan rarely wades into politics, but information technology has made exceptions, virtually notably past campaigning for aforementioned-sex marriage (legal in Iceland since 2010) and against a serial of hydro-electrical dams, which were built despite concerns nearly their impact on the surround. The faith likewise championed an Icelandic Forestry Clan-scheme to reforest parts of the country, where three million copse are being planted annually mainly for the proficient of nature but too, potentially, for timber production.

The Ásatrú faith celebrates Old Norse mythology and its pantheon of morally cryptic deities such as Odin (pictured), Thor and Loki (Credit: The Picture show Art Collection/Alamy)

Some of the older trees in the scheme will be used to make a roof for the Ásatrú Clan's new hof (temple), which is currently being built on the outskirts of Reykjavik. "It will be the first edifice made from Icelandic timber," Hilmarsson claimed proudly, as he gave me a tour of the site. "It's just in the last few years that we've had trees big enough to produce timber in Iceland."

The hof volition be the starting time pagan temple to be built in Iceland for most i,000 years, and will primarily be used to conduct marriages, funerals and name-giving ceremonies – events that are currently conducted outdoors. The edifice, which sits below ground level, is partially hewn from rock and descending into it, Hilmarsson claimed, will "symbolise a journey into the underworld".

The hof has been partially funded by Republic of iceland's taxpayers, who take to pay the government a religious tax, which is then distributed to official faith groups (hence why recognition was then important).

Respect for nature is important to the Ásatrú Association, which championed an try to reforest parts of the state (Credit: Chill IMAGES/Alamy)

The temple has been beset by delays, but Hilmarsson hopes that when it is finished – maybe this yr – it will attract not only locals but too tourists, who he claims are showing ever-increasing involvement in the Ásatrú faith.

"Nosotros accept open up house meetings most Saturdays, advertised on Facebook, and sometimes, in the summer, we have more foreigners there than locals," he said. "Hospitality is one of our master tenants and we always welcome everybody who comes." Open house meetings typically involve sitting around drinking tea, eating block and chatting. During the winter, there are too lectures, which accept previously covered subjects as diverse equally creativity, ecology and ethics.

But it is the blóts that offer perhaps the most bright insight into the Ásatrú faith. Held half-dozen times a year, the primary ones – Sigurblót, Þingblót, Haustblót and Jólablót – happen in April, June, Oct and December, respectively. Then in that location's Þorrablót and Vættablót, in January/February and December.

"Þorrablót is about getting drunk to gloat making it through the winter," said Hilmarsson. And Vættablót? That was introduced, he said, as a response to the Icelandic banking crash in 2008. "The nation was in trauma," he explained, claiming the blót was started as a social issue to cheer people upwards and encourage collective soul searching. "Although soul searching is non a national pastime," he added, dryly.

The Ásatrú Association has no religious doctrine, but it does promote virtuous behaviour (Credit: Gunnar Freyr Steinsson/Alamy)

That day, I was attention Sigurblót, and, after the service, the congregation made its fashion down to the beach for a banquet. I had expected local delicacies such as fermented shark, ram's testicles and puffin, but it was hotdogs, lager and candyfloss. The other stuff is typically served at Þorrablót, Hilmarsson explained. "That's when people swallow the obnoxious and horrible nutrient," he said, looking suitably disgusted, some other beer in his hand. "We also do vegan."

During the feast, I mingled with the congregation to detect out what attracted people to the faith. For Ásdís Elvarsdóttir, who was wrapped in a brilliant ruby coat, it was the sense of community and inclusivity. "I'm getting to know a lot of people through this – very proficient people," she said, her white hair bravado in the breeze. "Everyone is welcome – you don't accept to worry near being the strangest person in the grouping."

Echoing her sentiments was Alda Vala, whom I found perched on a bench, layered in colourful woollen fabrics and draped in fur. Vala has been an Ásatrú priest for 4 years, she told me, and was attracted to the organized religion by its openness.

"We have everyone without relation to gender, race or faith," she said, which reminded me of the Buddhist and Hindu guests I had been introduced to earlier ('brothers' equally Hilmarsson described them). "There are no rules – yous but accept to exist yourself."

Alda Vala, an Ásatrú priest, was attracted to the faith past its openness (Credit: Gavin Haines)

For Bragason, the well-coiffed priest, the Ásatrú religion was nearly making connections with people and nature through stories. "I tend to look at this like a cosy volume society," he said, looking smart in a padded jacket and patterned scarf. "Considering that'due south what all this is most really – storytelling."

Our Unique Earthis a BBC Travel serial that celebrates what makes us different and distinctive by exploring offbeat subcultures and obscure communities around the world.

Bring together more three million BBC Travel fans past liking u.s.a. onFacebook, or follow u.s. onTwitter andInstagram.

If you liked this story,sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Upper-case letter and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Source: https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20190602-how-iceland-recreated-a-viking-age-religion

0 Response to "Iceland Is Officially Worshiping Norse Gods Again"

إرسال تعليق