Robotic Assisted Thoracic Surgery for Early Stage Lung Cancer a Review

- Review

- Open Admission

- Published:

Feasibility and prophylactic of robot-assisted thoracic surgery for lung lobectomy in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis

World Journal of Surgical Oncology volume xv, Article number:98 (2017) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

The aim of this written report is to evaluate the feasibility and safety of robot-assisted thoracic surgery (RATS) lobectomy versus video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) for lobectomy in patients with non-small jail cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Methods

An electronic search of six electronic databases was performed to place relevant comparative studies. Meta-analysis was performed by pooling the results of reported incidence of overall morbidity, bloodshed, prolonged air leak, arrhythmia, and pneumonia between RATS and VATS lobectomy. Subgroup analysis was as well conducted based on matched and unmatched cohort studies, if possible. Relative risks (RR) with their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated by ways of Revman version 5.3.

Results

Twelve retrospective accomplice studies were included, with a total of 60,959 patients. RATS lobectomy significantly reduced the mortality rate when compared with VATS lobectomy (RR = 0.54, 95% CI 0.38–0.77; P = 0.0006), just this was not consistent with the pooled issue of six matched studies (RR = 0.12, 95% CI 0.01–i.07; P = 0.06). There was no significant difference in morbidity between the two approaches (RR = 0.97, 95% CI 0.85–ane.12; P = 0.70).

Conclusions

RATS lobectomy is a feasible and safe technique and can achieve an equivalent short-term surgical efficacy when compared with VATS, but its cost effectiveness too should be taken into consideration.

Background

Lobectomy is considered to be the standard therapy for patients with non-pocket-size cell lung cancer (NSCLC) at an early on stage, and a minimally invasive approach such as video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS), rather than thoracotomy, has been recommended to this group of patients [1]. Since the initial VATS lobectomy described in the early on 1990s [2, three], growing evidence has suggested that VATS is an advisable arroyo, which shows superior perioperative outcomes and improved long-term survival for selected patients with early on phase NSCLC when compared with conventional thoracotomy [4, five]. Despite such demonstrated advantages of VATS, some shortcomings such as steep learning curve, difficult hand-center coordination, lack of instrument flexibility, and two-dimensional vision might nevertheless restrict the evolution of this technique [6, 7].

Robot-assisted thoracic surgery (RATS) is a relatively new technique for minimally invasive lung lobectomy. And the initial feasibility and safety of RATS lobectomy take been described by several publications in the past 10 years [8,ix,10,11]. RATS lobectomy appears to present some advantages of VATS approach in terms of decreased claret loss, less impairment in pulmonary function, and short hospital length of stay when compared to conventional thoracotomy [12,xiii,14]. Nonetheless, RATS lobectomy may exist limited past its potential longer operative fourth dimension and higher infirmary costs. Ignoring these disadvantages, advocates still emphasize the benefits of RATS in regard to iii-dimensional high-definition view, improved ergonomics less steep learning curve, and better maneuverability of instruments [15, 16]. Unfortunately, there is lack of evidence-based information on the feasibility and safety of RATS lobectomy in patients with NSCLC and whether RATS lobectomy tin can attain equivalent short-term surgical efficacy when compared with VATS is also unknown. Therefore, nosotros conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis of published studies in an attempt to assess the feasibility and safe of RATS lobectomy versus those with VATS.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

Electronic searches were performed in PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane Fundamental Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and ClinicalTrials.gov up to December 2016 without language restriction. We combined the terms "VATS OR video-assisted thoracic surgery OR thoracoscopic surgery" and "robotics OR robot OR robotic surgery OR figurer-assisted surgery OR da Vinci" to search for eligible comparative studies. References of included studies were also manually searched to identify potentially relevant studies.

Study selection

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) period chart was adapted to describe the written report selection process [17]. Later on removing duplicates, two reviewers (SYW and MHC) independently reviewed the relevant studies by checking the titles, abstracts, and full-texts. Studies were eligible for inclusion in this meta-analysis if they were randomized or not-randomized controlled trials comparing RATS to VATS. Nosotros excluded studies which were relevant to RATS wedge resection or segmentectomy and those which did non incorporate a comparative grouping. In the instance of duplicate publications with accumulating numbers of patients or increased lengths of follow-up, we only included the near recent or complete reports for our analysis.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (SYW and MHC) independently examined the included studies and extracted data points pertaining to get-go author's name, year of publication, study design, study period, surgical technique for RATS or VATS lobectomy, preoperative patient demographics (number of patients, geographic location, lobe distribution, and pathological phase), intraoperative parameters (operative fourth dimension, blood loss, and conversion), and postoperative parameters (dissected lymph nodes station and number, hospital length of stay, prolonged air leak, arrhythmia, pneumonia, composite morbidity, perioperative mortality, and costs). The primary outcomes were perioperative mortality and morbidity, and the secondary outcomes were operative time, blood loss, hospital length of stay, prolonged air leak, arrhythmia, pneumonia, conversion, dissected lymph nodes (LNs) station and number, and costs. Discrepancies were resolved by grouping give-and-take and consensus with a senior investigator (LXL).

Quality assessment

The risk of bias for each included observational written report was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Calibration (NOS). The NOS includes three parts for cohort studies: selection (four scores assigned), comparability (two scores assigned), and effect (three scores assigned). Studies with scores of 0 to iii, 4 to half-dozen, and vii to nine were considered to be low, moderate, and high quality, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Meta-analysis was performed past pooling the results of reported incidence of overall morbidity, mortality, prolonged air leak, arrhythmia, and pneumonia. Subgroup analysis was likewise conducted based on matched and unmatched cohort studies, if possible. Relative risks (RR) and their 95% conviction intervals (CI) were calculated for discontinuous data. Summary RRs were calculated by using fixed-effect models when heterogeneity among studies was considered to be statistically insignificant. Otherwise, random-effect models were used to combine the results. Heterogeneity amid the studies was identified by conducting a standard Cochrane'south Q test with a significance level of α = 0.ten. The I two statistic test was performed to farther examine heterogeneity. I ii ≥ 50% was considered to bespeak substantial heterogeneity. Besides, visual inspection of the funnel plots was used to identify potential publication bias. All P values were 2-tailed, and P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All assay was conducted with Review Manager Version five.3 (Cochrane Collaboration, Software Update, Oxford, United Kingdom, 2014).

Results

Literature search

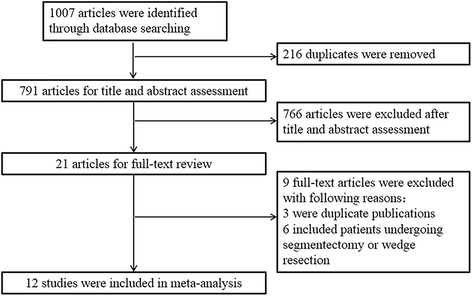

The initial search identified 1007 references. Later on duplicates were removed, 791 articles were retrieved for title and abstract assessment, and 21 articles were selected for full-text evaluation. Nine manufactures were excluded; of which, 3 articles were indistinguishable publications and six articles were relevant to RATS segmentectomy or wedge resection. Finally, a total of 12 retrospective cohort studies were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis [18,nineteen,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. The flow chart of selection for included studies is depicted in Fig. 1.

The PRISMA menstruation chart of choice for included studies

Characteristics and risk of bias assessment

The included studies were published from 2010 to 2017. Of the 12 studies, seven studies [21, 23,24,25,26, 28, 29] were conducted in North America, two [22, 27] in Europe, two [18, nineteen] in Asia, and ane [20] in Australia. Overall, threescore,959 patients were identified for the analysis; of whom, 4727 patients underwent RATS and 56,232 patients received VATS lobectomy. The boilerplate age beyond various studies ranged from 26 to 88 years onetime. Of the 12 included studies, eight [18,19,20,21,22, 26,27,28] referred to the surgical technique of RATS, seven [18,19,xx,21, 26,27,28] reported the arms of the da Vinci surgical system, and only five [18, 21, 26,27,28] provided information about the blazon of da Vinci surgical organization.

The quality of the included studies assessed by the NOS was generally adequate, with a mean NOS scores of 6.8 (standard deviation = 0.vii). For most included studies, the methodological quality in terms of accomplice selection and comparability was adequate. However, the follow-up periods were limited for most studies except for two studies [26, 28]. The characteristics and risk of bias cess of the included studies were shown in Table 1

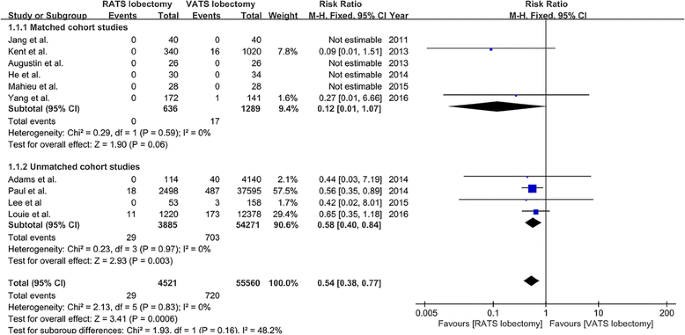

Assessment of perioperative outcomes

A full of ten studies [xviii, 20,21,22,23,24, 26,27,28,29] that compared RATS to VATS lobectomy reported perioperative mortality issue, including half dozen matched studies [eighteen, 20, 22, 23, 27, 28] and four unmatched studies [21, 24, 26, 29]. Mortality was 0.vi% (29/4521) and 1.three% (720/55,560) for patients undergoing RATS and VATS, respectively. The pooled analysis of bloodshed demonstrated that when compared to VATS lobectomy, RATS showed a significantly lower mortality (RR = 0.54, 95% CI 0.38–0.77; P = 0.0006; fixed model), and this result was in line with the pooled consequence of three unmatched studies (RR = 0.58, 95% CI 0.40–0.84; P = 0.003), but was not consistent with the pooled issue of half-dozen matched studies (RR = 0.12, 95% CI 0.01–1.07; P = 0.06) (Fig. 2). There was no statistical heterogeneity among the studies (I 2 = 0%, P = 0.83). Visual inspection of the funnel plots did not identify a potential publication bias.

The forest plot and meta-assay of mortality for patients undergoing RATS versus VATS lobectomy

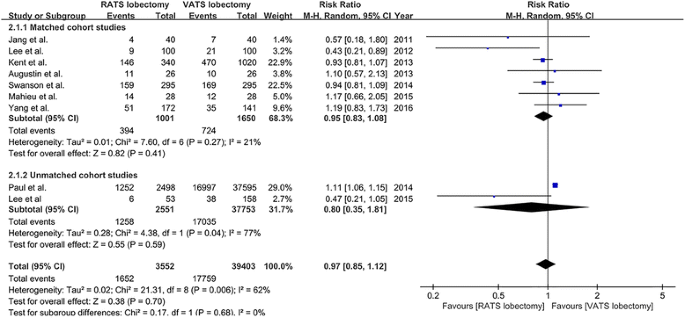

Composite morbidity was reported in nine studies [18,19,20, 23,24,25,26,27,28] (vii matched studies [xviii,19,20, 23, 25, 27, 28] and 2 unmatched studies [24, 26]). The overall morbidity charge per unit was 46.5% (1652/3552) and 45.1% (17,759/39,403) in patients who underwent RATS and VATS lobectomy, respectively. The result of meta-analysis revealed that in that location was no statistically significant departure in composite morbidity betwixt RATS and VATS lobectomy (RR = 0.97, 95% CI 0.85–1.12; P = 0.70; random model), and there was a significant heterogeneity amidst the eight studies (I 2 = 62%, P = 0.006) (Fig. iii). Publication bias was not evident from visual inspection of the funnel plots.

The forest plot and meta-analysis of composite morbidity for patients undergoing RATS versus VATS lobectomy

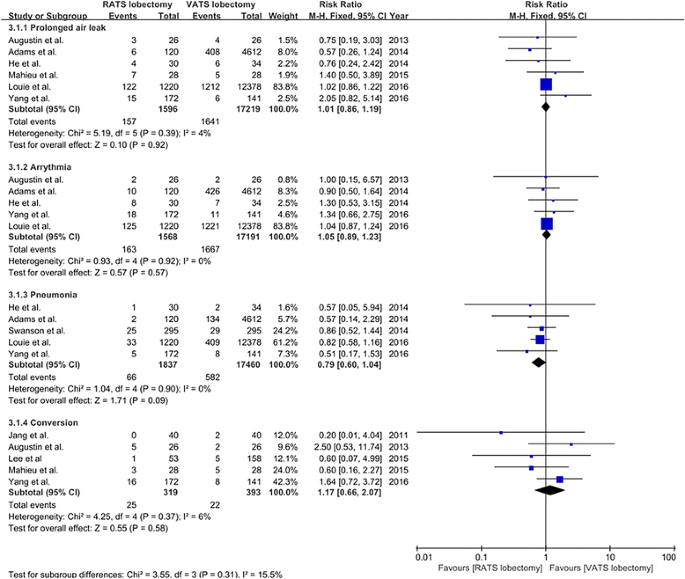

Prolonged air leak was reported in six studies [20,21,22, 27,28,29], and the incidence of prolonged air leak was 9.8% (157/1596) and 9.5% (1641/17,219) for patients undergoing VATS and RATS, respectively. The incidence of arrhythmia that was reported in five studies [20,21,22, 28, 29] was 10.4% (163/1568) for RATS lobectomy and 9.seven% (1667/17,191) for VATS lobectomy. Five studies [21, 22, 25, 28, 29] reported the data on the incidence of pneumonia, which was three.6% (66/1837) and 3.3% (582/17,460) for patients undergoing RATS and VATS lobectomy, respectively. 5 studies [eighteen, 20, 26,27,28] provided the charge per unit of conversion, and the incidence of conversion was 7.8% (25/319) and 5.six% (22/393) for RATS and VATS lobectomy, respectively. The meta-analysis on prolonged air leak, arrhythmia, pneumonia, and conversion all showed no meaning differences between RATS and VATS lobectomy (prolonged air leak RR = 1.01, 95% CI 0.86–1.19, P = 0.92; arrhythmia RR = 1.05, 95% CI 0.89–1.23, P = 0.57; pneumonia RR = 0.79, 95% CI 0.60–1.04, P = 0.09; conversion RR = 1.17, 95% CI 0.66–2.07, P = 0.58; stock-still model) (Fig. four).

The forest plot and meta-assay of subtype morbidity for patients undergoing RATS versus VATS lobectomy

For the 12 studies [xviii,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29] that compared RATS to VATS lobectomy, operative time was significantly longer in RATS group in half dozen studies [18,19,20,21, 26, 29], shorter in one study [22], no difference in two studies [25, 27], and not reported in three studies [23, 24, 28]. No significant difference was found in blood loss between RATS and VATS lobectomy in two studies [xviii, 27]. Only one report [nineteen] showed a significant shorter hospital length of stay when comparing RATS to VATS lobectomy, and 10 studies [18, 20, 21, 23,24,25,26,27,28,29] did not observed a departure betwixt the two approaches. The number of dissected lymph nodes station ranged from five to 7 and the number of removed lymph nodes ranged from 14 to 24 for RATS lobectomy, which were comparable to VATS lobectomy. However, costs were significantly increased for RATS lobectomy in the included studies (Table 2).

Discussion

Since the first utilize of the da Vinci robotic surgical system for pulmonary lobectomy which was reported in 2002 [30], several studies [8, 9] have showed the feasibility and safety of this novel technique for lobectomy. A systematic review performed by Cao et al. [31] showed that perioperative mortality for patients who underwent pulmonary resection by RATS ranged from one to iii.8% and overall morbidity ranged from 10 to 39%. However, Cao et al. did not conduct a pooled analysis to appraise the safety and efficacy of RATS lobectomy compared to those of VATS lobectomy. In another study [32], eight retrospective observational studies were eligible for meta-analysis and were evaluated for perioperative morbidity and bloodshed, but the meta-analysis included patients who underwent lobectomy, segmentectomy, and wedge resection.

The present systematic review and meta-analysis identified twelve retrospective cohort studies, including a total of 60,959 patients who underwent RATS lobectomy (north = 4727) and VATS lobectomy (due north = 56,232). The meta-assay revealed that RATS lobectomy significantly reduced the mortality charge per unit when compared with VATS lobectomy (RR = 0.54, 95% CI 0.38–0.77; P = 0.0006), but this was not consistent with the pooled consequence of six matched studies (RR = 0.12, 95% CI 0.01–ane.07; P = 0.06). This result could exist explained in part by the highly selected patients at the beginning of this surgical technique; therefore, this effect should be interpreted with circumspection. Moreover, the overall perioperative morbidity rate of RATS was similar to that of VATS lobectomy, and no statistically significant differences were observed in the incidence of postoperative prolonged air leak, arrhythmia, and pneumonia when comparison RATS to VATS lobectomy. Anyway, these outcomes suggest that RATS lobectomy is a safe and feasible surgical approach for patients with lung cancer and can achieve an equivalent short-term surgical efficacy compared with VATS lobectomy.

With respect to the operative results, most included studies reported a longer operative time for RATS compared to VATS lobectomy [18,19,20,21, 26, 29]. This can be explained by several potential factors. Beginning, the knowledge and experience of RATS lobectomy for surgeons were inadequate at the beginning of the learning curve and about included studies just reported their initial attempts to RATS lobectomy. Second, prolonged operative time was reported to exist caused by setting upwardly the robotic system [18, 20]. 3rd, different surgery approaches might lead to different operative fourth dimension. As reported in the report of Augustin et al. [20], the overall operative time was longer in the RATS group, only when comparing the anterior approach of RATS to VATS lobectomy, at that place was no meaning difference on operative fourth dimension. But it should be mentioned that the increased operative time in robotic surgery did not seem to have a negative bear on on postoperative results, since there was no increment in short-term morbidity and mortality for patients. Likewise, operative time for RATS approach has been shown to significantly shorten after the initial learning menses. Therefore, with the increased knowledge and feel of RATS, operative time for RATS would be comparable to VATS.

In addition, in our present study, college costs for lung lobectomy with the da Vinci surgical arrangement was observed in most included studies. In a large case series, Park et al. [33] demonstrated that RATS lobectomy was on average $3981 more than expensive than VATS lobectomy, but $3988 cheaper than open up lobectomy. And the increased costs of RATS compared with VATS lobectomy occurred primarily in the offset hospital twenty-four hour period, which could be explained as the additional disposable costs of the robotic instruments and a higher percentage of additional procedural costs. Augustin et al. [twenty] also indicated that two thirds of the additional costs for RATS lobectomy were acquired by disposables and the utilise of robotic instruments. However, in a retrospective analysis of 176 RATS lobectomies compared to 76 VATS lobectomies, Dylewski et al. [34] showed that direct costs was reduced by $560 per instance in RATS group. And the majority of costs saving benefited from reduced length of hospital stay and lower overall nursing care costs. In addition, according to Deen et al. [35], shortening operative time, eradicating unnecessary laboratory piece of work, reducing respiratory therapy, and minimizing stays in the intensive care unit would contribute to a decrease of hospital costs for patients who underwent RATS lobectomy. However, the costs associated with the overall substantial conquering and maintenance for the robotic system was usually not included in analysis in nearly studies. In fact, a da Vinci robotic surgical organisation currently costs between $one and $two.5 million in the Us [36], and is associated with annual maintenance costs of approximately $100,000 to $170,000 [33, 37]. Therefore, in the Japanese health care organisation, it is necessary to perform at least 300 robotic operations per year in each institution to avoid fiscal deficit with the current process of robotic surgical system management [38]. Since the effectiveness of RATS lobectomy is equivalent with increased costs when compared with that of VATS procedure, manufacturers of robotic surgical organisation would reduce supply costs by developing new generation robotic organization to be more competitive.

There are several limitations existing in the present systematic review and meta-analysis. Firstly, it should be acknowledged that the data included in the present meta-analysis were extrapolated from 12 retrospective accomplice studies. Although the heterogeneity was negligible among the included studies, selection bias of retrospective studies may lead to unbalanced selection of patients. Secondly, the characteristics of included patients and the surgical techniques were non conspicuously described in some included studies, which may lead a bias for the meta-analysis results. Thirdly, specific criteria for the definition of outcomes, such as prolonged air leak, conversion, and morbidity, were non clearly stated in about included studies. Fourthly, there are lacks of long-term follow-up outcomes for the comparing of RATS lobectomy with VATS lobectomy. Hence, time to come studies should emphasize the rigorous eligibility criteria, articulate definition of outcomes, and long-term follow-up data.

Conclusions

In decision, the electric current systematic and meta-analysis demonstrates that RATS lobectomy is a feasible and safe technique for selected patients and tin can achieve an equivalent short-term surgical efficacy when compared with VATS procedure. However, longer operative time and cost effectiveness of RATS should be taken into consideration, and long-term oncological efficacy of the RATS approach remains to be seen.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CPRL:

-

Completely portal robot lobectomy

- LNs:

-

Lymph nodes

- NA:

-

Not available

- NOS:

-

Newcastle-Ottawa Calibration

- NSCLC:

-

Non-small prison cell lung cancer

- RAL:

-

Robot-assisted lobectomy

- RATS:

-

Robot-assisted thoracic surgery

- RCS:

-

Retrospective cohort study

- RR:

-

Relative risks

- VATS:

-

Video-assisted thoracic surgery.

References

-

Detterbeck FC, Lewis SZ, Diekemper R, et al. Executive summary: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Breast. 2013;143:7S–37S.

-

Kirby TJ, Mack MJ, Landreneau RJ, et al. Initial experience with video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1993;56:1248–52. discussion 52–iii.

-

Walker WS, Carnochan FM, Pugh GC. Thoracoscopic pulmonary lobectomy. Early operative experience and preliminary clinical results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1993;106:1111–seven.

-

Yan TD, Black D, Bannon PG, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and nonrandomized trials on safe and efficacy of video-assisted thoracic surgery lobectomy for early-phase non-small-scale-prison cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2553–62.

-

Cao C, Manganas C, Ang SC, et al. A meta-analysis of unmatched and matched patients comparing video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy and conventional open up lobectomy. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;1:16–23.

-

Petersen RH, Hansen HJ. Learning curve associated with VATS lobectomy. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;1:47–50.

-

Arad T, Levi-Faber D, Nir RR, et al. The learning bend of video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) for lung lobectomy—a unmarried Israeli center experience. Harefuah. 2012;151:261–5. 320.

-

Park BJ, Flores RM, Rusch VW. Robotic assistance for video-assisted thoracic surgical lobectomy: technique and initial results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131:54–9.

-

Gharagozloo F, Margolis M, Tempesta B, et al. Robot-assisted lobectomy for early-stage lung cancer: report of 100 consecutive cases. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:380–4.

-

Augustin F, Bodner J, Wykypiel H, et al. Initial feel with robotic lung lobectomy: report of two different approaches. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:108–13.

-

Kumar A, Asaf BB, Cerfolio RJ, et al. Robotic lobectomy: the first Indian study. J Minim Access Surg. 2015;11:94–8.

-

Veronesi Thou, Galetta D, Maisonneuve P, et al. Four-arm robotic lobectomy for the handling of early-stage lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140:19–25.

-

Cerfolio RJ, Bryant AS, Skylizard 50, et al. Initial consecutive experience of completely portal robotic pulmonary resection with four arms. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;142:740–6.

-

Oh DS, Cho I, Karamian B, et al. Early adoption of robotic pulmonary lobectomy: feasibility and initial outcomes. Am Surg. 2013;79:1075–80.

-

Melfi FM, Fanucchi O, Davini F, et al. VATS-based arroyo for robotic lobectomy. Thorac Surg Clin. 2014;24:143–9. 5.

-

Veronesi Thou. Robotic thoracic surgery: technical considerations and learning curve for pulmonary resection. Thorac Surg Clin. 2014;24:135–41. v.

-

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700.

-

Jang HJ, Lee HS, Park SY, et al. Comparison of the early robot-assisted lobectomy feel to video-assisted thoracic surgery lobectomy for lung cancer: a unmarried-institution case series matching study. Innovations (Phila). 2011;6:305–10.

-

Lee HS, Jang HJ. Thoracoscopic mediastinal lymph node autopsy for lung cancer. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;24:131–41.

-

Augustin F, Bodner J, Maier H, et al. Robotic-assisted minimally invasive vs. thoracoscopic lung lobectomy: comparison of perioperative results in a learning bend setting. Langenbecks Curvation Surg. 2013;398:895–901.

-

Adams RD, Bolton WD, Stephenson JE, et al. Initial multicenter customs robotic lobectomy feel: comparisons to a national database. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97:1893–eight. word 1899–1900.

-

He Y, Coonar A, Gelvez-Zapata S, et al. Evaluation of a robot-assisted video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery program. Exp Ther Med. 2014;7:873–6.

-

Kent Thou, Wang T, Whyte R, et al. Open up, video-assisted thoracic surgery, and robotic lobectomy: review of a national database. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97:236–42. give-and-take 242–iv.

-

Paul South, Jalbert J, Isaacs AJ, et al. Comparative effectiveness of robotic-assisted vs thoracoscopic lobectomy. Chest. 2014;146:1505–12.

-

Swanson SJ, Miller DL, McKenna Jr RJ, et al. Comparing robot-assisted thoracic surgical lobectomy with conventional video-assisted thoracic surgical lobectomy and wedge resection: results from a multihospital database (Premier). J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;147:929–37.

-

Lee BE, Shapiro M, Rutledge JR, et al. Nodal upstaging in robotic and video assisted thoracic surgery lobectomy for clinical N0 lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100:229–33. word 233–four.

-

Mahieu J, Rinieri P, Bubenheim M, et al. Robot-assisted thoracoscopic surgery versus video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for lung lobectomy: can a robotic approach improve short-term outcomes and operative safety? Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;4:354–62.

-

Yang HX, Woo KM, Sima CS, et al. Long-term survival based on the surgical approach to lobectomy for clinical stage I nonsmall cell lung cancer: comparing of robotic, video-assisted thoracic surgery, and thoracotomy lobectomy. Ann Surg. 2017;265:431–7.

-

Louie BE, Wilson JL, Kim S, et al. Comparison of video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery and robotic approaches for clinical stage I and phase Two non-small cell lung cancer using the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Database. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;102:917–24.

-

Melfi FM, Menconi GF, Mariani AM, et al. Early experience with robotic applied science for thoracoscopic surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;21:864–8.

-

Cao C, Manganas C, Ang SC, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on pulmonary resections past robotic video-assisted thoracic surgery. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;1:3–10.

-

Ye 10, Xie L, Chen G, et al. Robotic thoracic surgery versus video-assisted thoracic surgery for lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2015;21:409–14.

-

Park BJ, Flores RM. Cost comparison of robotic, video-assisted thoracic surgery and thoracotomy approaches to pulmonary lobectomy. Thorac Surg Clin. 2008;xviii:297–300. seven.

-

Dylewski MR, Lazzaro RS. Robotics—the answer to the Achilles' heel of VATS pulmonary resection. Mentum J Cancer Res. 2012;24:259–60.

-

Deen SA, Wilson JL, Wilshire CL, et al. Defining the cost of care for lobectomy and segmentectomy: a comparison of open, video-assisted thoracoscopic, and robotic approaches. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97:1000–7.

-

Turchetti G, Palla I, Pierotti F, et al. Economic evaluation of da Vinci-assisted robotic surgery: a systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:598–606.

-

Wei B, D'Amico TA. Thoracoscopic versus robotic approaches: advantages and disadvantages. Thorac Surg Clin. 2014;24:177–88. vi.

-

Kajiwara Due north, Patrick Barron J, Kato Y, et al. Price-benefit performance of robotic surgery compared with video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery under the Japanese National Health Insurance System. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;21:95–101.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

All information generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

SYW, MHC, and LXL contributed to the study conception and design. SYW and MHC performed the collection of data. SYW, MHC, and NC conducted the information analysis and interpretation. All authors contributed to the manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

None.

Ideals blessing and consent to participate

None.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding writer

Rights and permissions

Open Access This commodity is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(southward) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Artistic Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/ane.0/) applies to the data made bachelor in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Well-nigh this article

Cite this article

Wei, S., Chen, K., Chen, N. et al. Feasibility and prophylactic of robot-assisted thoracic surgery for lung lobectomy in patients with not-small jail cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Globe J Surg Onc fifteen, 98 (2017). https://doi.org/ten.1186/s12957-017-1168-six

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-017-1168-six

Keywords

- Robot-assisted thoracic surgery

- Video-assisted thoracic surgery

- Minimally invasive surgery

- Lung lobectomy

Source: https://wjso.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12957-017-1168-6

0 Response to "Robotic Assisted Thoracic Surgery for Early Stage Lung Cancer a Review"

إرسال تعليق